There I was, bike straddled between sunburned legs, my equally reddened arms resting heavily on the handlebars, wondering what on earth I was getting myself into.

There I was, bike straddled between sunburned legs, my equally reddened arms resting heavily on the handlebars, wondering what on earth I was getting myself into.by Ryan Parton

The Edmonton Journal, June 22, 2002

There I was, bike straddled between sunburned legs, my equally reddened arms resting heavily on the handlebars, wondering what on earth I was getting myself into.

There I was, bike straddled between sunburned legs, my equally reddened arms resting heavily on the handlebars, wondering what on earth I was getting myself into.

I stood at the large, uncontrolled intersection of Belize's Hummingbird and Southern Highways, looking south down a dusty, pot-holed road with a grove of scraggly orange trees on one side and what looked like barren scrub land on the other. The air was hot and sickly sweet, like I had opened a giant package of Tang crystals and was breathing the fumes. At the end of this uninviting road, some 160 kilometres away, lay Punta Gorda, Belize's southernmost town of any significance and my ultimate destination.

I pointed my bike south and started pedalling.

It was quite by random that I had chosen Belize for my annual escape to the sun. I knew virtually nothing about this tiny country except that I liked the way its name rolled off my tongue, exotic and mysterious.

I did some research and quickly became fascinated by this country that touts itself as "Mother Nature's best-kept secret." In an area roughly the size of New Hampshire, Belize has a population of only about 240,000, making it the most sparsely populated country in Central America. Full of vast jungles, cascading waterfalls and awesome limestone caves, it sounded to me like an unforgettable adventure waiting to happen.

The Belizean cayes, speckling the Caribbean Sea along the country's eastern flank, have long been popular with North American beach-seekers. But I wasn't seeking a beach. I was on a quest for adventure, determined to discover the raw, sweaty, untamed Belize.

And I was going to do it on my bike.

I imagined myself pedalling down rolling asphalt, cutting through dense, green jungle, brightly coloured toucans flying overhead and families of playful howler monkeys scurrying among the trees. I was ready for a true jungle adventure. I wasn't ready for the Southern Highway.

Before my introduction to the dusty Southern Highway, my trip had more or less been living up to my lofty expectations, save for the monkeys and the toucans. But after the beautiful countryside of Belize's rugged, jungly Cayo District, the opening stretch of the Southern Highway was anti-climactic to say the least.

I cycled past a putrid-smelling garbage dump and over several narrow bridges spanning dirty-looking streams, all the while trying not to notice the row upon row of those ugly orange trees, which wouldn't have looked out of place in one of Tim Burton's surreal nightmares. If things kept up like this, it was going to be a long ride.

Shortly after noon I arrived at the turnoff to to Hopkins, a picturesque village tucked away along the Caribbean coast about eight rock-strewn kilometres from the highway. As I wove my way through the maze of rocks and ruts I came within a foot of running over a large, rather nefarious-looking fer-de-lance, Central America's most notorious serpent, sunning itself in the middle of the road. I decided to pay more attention to where I was going.

Hopkins is a sleepy little place where there's nothing to do and all day to do it, the perfect place to grab a Belikin, Belize's local brew, and fall back into a seaside hammock to rest a saddle-weary bottom.

I set out bright and early the following morning for Placencia, roughly 75 kilometres of bumpy roads away at the end of a thin, serpentine peninsula.

After 40 kilometres of bouncing painfully down the highway, past monochrome scrub land, a couple of small banana plantations and more of those scraggy orange trees, I turned left towards Placencia and was relieved to find the new road a tad less rough.

I was quickly irritated, however, by a continuous flow of large gravel trucks that kicked up thick clouds of eye-stinging red dust as they thundered past, displaying little sympathy or consideration towards an insignificant cyclist.

My map showed Placencia's peninsula as a thin strip of land which in some places looked no wider than the road itself, and for weeks I had been looking forward to cycling its length. I had imagined smooth blacktop with sandy white beaches on either side, the pristine turquoise sea just a stone's throw away.

In reality, there is no blacktop, no beach and no sea at which to throw stones. It's the same brutal dirt track, with the added difficulty of wheel-snatching sandy stretches, and any magnificent seascapes are blocked by a thin, yet impossibly dense, layer of trees.

I arrived in Placencia hot, dirty and in a decidedly rotten mood. I contemplated giving in and spending my last three days in Belize lounging on the beach, with the cool sea breeze blowing against my face. But I wouldn't let myself do it. The plan was to get to Punta Gorda, and I would stick to the plan.

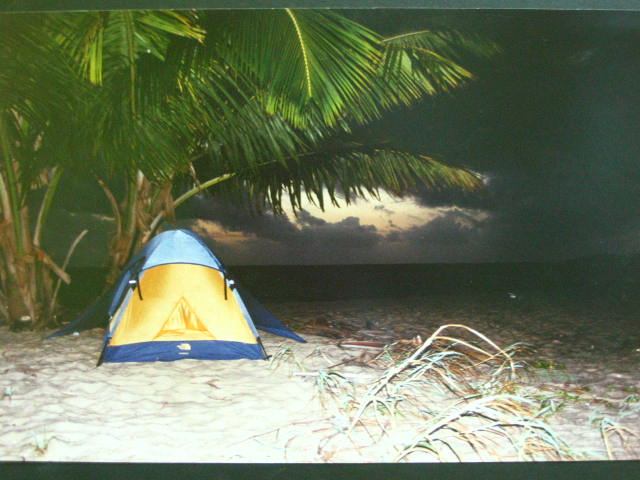

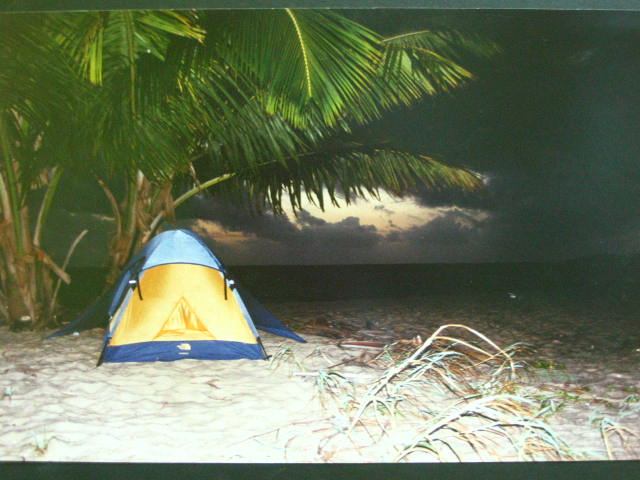

After a gusty night that threatened to blow my tiny tent right off the beach, I pushed my bike down the long sidewalk that is Placencia's main drag and caught the daily ferry to Independence Village, where I rejoined my old friend, the Southern Highway, for the home stretch.

I was prepared to hate this day's ride, to arrive in Punta Gorda foul-tempered and exhausted. But something had changed. It wasn't the road, for it was as mean as ever, with the added hassle of detours and loose gravel, the result of an extensive project to eventually pave the Southern Highway's entire length.

Something within me was different. Somewhere back in Placencia, back on the beach, I had undergone some silent, entirely subconscious, transformation.

Perhaps it was the reinvigorating sea air, or the peaceful solitude that comes with lolling on the beach under a lazy palm. Or maybe it was the promise of a hotel room in Punta Gorda, followed by cold beverage service on my flight home. Whatever it was, it altered dramatically the way I saw the Southern Highway.

I had come to accept this road, in all its rough-and-tumble glory. I was cycling past the same, desolate scrub land, but it was suddenly beautiful. The road was deserted save for the occasional bus rattling past me towards Punta Gorda, or heading north to Independence. I was in Butt Smack Nowhere, Belize. I was on a bike, and I was truly free.

I chewed up the miles, past towering pine trees and tiny Mayan villages, stopping periodically to buy bottled water from thatched-roof huts with Coca-Cola signs hung by the doorway.

I cheerfully called "Good morning!" to the villagers I passed, who would return my greeting with a "Hello!" or a "Buenos!" or a "Heeeeeyyy!" I cycled over small wooden bridges and waved at the women washing clothes in the river below. Almost without thinking, I deftly navigated the myriad of rocks and potholes, and not once did my fanny scream in protest as it had for the past two days.

Near the village of Big Falls, about 30 kilometres from my final destination, the Southern Highway became paved for good, but it didn't really matter. I was having the time of my life.

I pedaled into Punta Gorda, more than 600 kilometres of sub-tropical cycling now behind me. I should have felt proud, even celebratory, but neither of these emotions immediately came to me. The satisfaction of having completed my journey was overshadowed by the dispiriting realization that my adventure was over.

I didn't want to go home. Belize's warm, friendly faces and rugged natural beauty had touched me in a way I hadn't realized back in Placencia. I wanted to turn my bike around and do it all again.

In the next couple of years, the paving of the Southern Highway will likely be completed, an improvement eagerly anticipated by Belizean drivers. However, I can't help but feel a touch of sadness for that rocky, dusty road that carried me so far.